Blues Musician Sugar Brown Shares Globe-Trekking Odyssey With “Toronto Bound” Single And Album

Picking up and leaving for a new town or city can be a challenge at the best of times. But for Toronto-based blues musician Ken Kawashima (aka Sugar Brown), leaving Chicago — often considered one of the blues’ hotbeds — for Toronto seems like a natural fit on the groovy and gorgeous new single “Toronto Bound,” the title track of his latest studio album.

The song, inspired in part by the 1954 blues song “Chicago Bound” by Muddy Waters’ guitarist Jimmy Rogers, is a lyrical trek of Brown’s journey over the last few decades. From his hometown of Bowling Green, Ohio to Chicago to Paris to New York City to Tokyo and finally to Toronto, Sugar Brown (who was given the stage name by James Yancy Jones, better known in blues circles as Tail Dragger Jones) describes the fun-filled trip perfectly with a timeless blues foundation. Think of some fusion between John Lee Hooker, Little Walter, and a ramshackle Bob Dylan on a nearly seven-minute blues binge, and “Toronto Bound” becomes crystal clear.

In Toronto town

I got a job and pay

I got me a home

Where I can stay

But I need my baby

Or I need a new lover

Oh, I need my baby

Or I need a new lover

“This song tells the story of my itinerant life as I left many places: Ohio, Chicago, Paris, NYC, Tokyo…and ended up in Toronto, where I’ve resided since 2002,” Brown says of “Toronto Bound.” The single was naturally recorded in Toronto, with Brown using all Toronto musicians for both the single and the album Toronto Bound. And nearly all of the album was recorded on one hot, sweaty late-summer day in, you guessed it, Toronto.

“True to my production principles, we recorded the album live off-the-floor and onto one-inch magnetic tape,” Brown says of the creative process. “This is like jumping onto a fast-moving train without knowing where it is going.”

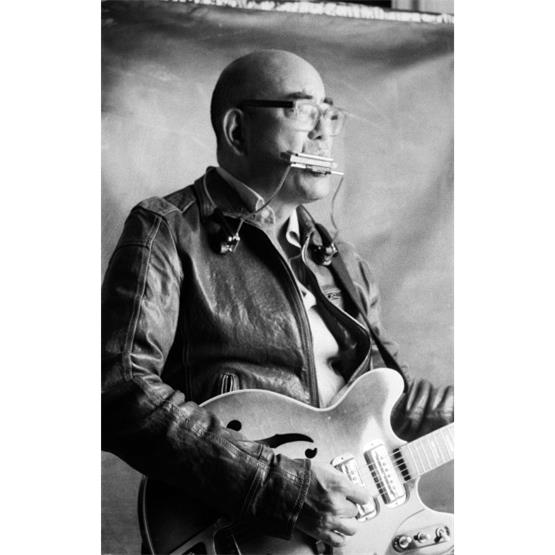

“Toronto Bound” features Brown on lead vocals, harmonica and electric guitar while guitarist Nichol Robertson, upright acoustic bassist Victor Bateman, drummer Lowell Whitty and percussionist Derek Thorne keep things chugging down the road Brown sings about.

“They are bad, bad, bad,” Brown says. “That’s why I like ’em. They also thrive on ‘composing on the fly,’ as Ornette Coleman said. And, like myself, they’re all bound to Toronto in one way or another. Toronto Bound is what this city sounds like to me.”

The child of a Japanese father and Korean mother, the musician began playing blues in Chicago when he was 19 while attending university. Playing with the likes of Tail Dragger Jones and later iconic Muddy Waters’ drummer Willie “Big Eyes” Smith, Sugar Brown left Chicago to become a historical researcher and university teacher. In fact, he’s currently a professor at the University of Toronto’s Department of East Asian Studies. But “the blues followed me into the next stage of my life,” Brown says, resulting in his 2011 debut album Sugar Brown’s Sad Day. Subsequent albums included 2015’s Poor Lazarus and 2018’s It’s A Blues World: Calling All Blues.

Having performed at various festivals, including the Montreal International Jazz Festival and the Edmonton Blues Festival, Sugar Brown has also regularly played at Toronto’s Grossman’s Tavern. Now Sugar Brown looks to take both “Toronto Bound” and the album of the same name to the masses. And judging by how appealing the classic-sounding lead single is, look for the song to be heard all over the place. Be it Ohio. Or Chicago. Or Paris. Or New York. Or Tokyo. Or Toronto.

Hi, Sugar! Good to meet you! Care to introduce yourself to the readers?

Hi, it’s a pleasure to meet you, too. I’ll try to introduce myself to your readers. Hi, I’m Sugar Brown and I live in Toronto, Ontario. I’m proudly Canadian and I play and sing the blues. I have a new album called Toronto Bound. It’s my fourth studio album and the first album I’ve released in over six years.I hope you can listen to it and enjoy the thirteen original songs that I’ve had the good fortune and great privilege of writing, composing, playing, and recording with some really incredible musicians in Toronto. I’ve been working and living in Toronto since 2002 when I was hired as a historian of modern Japan in the Department of East Asian Studies at the University of Toronto. I still work and teach there. I was born in Ohio in 1971, then moved to Chicago, flirted with Paris, studied in New York, lived and researched in Tokyo, and finally came to Toronto for gainful employment, for which I am very grateful. That’s why my album is called Toronto Bound. It turns out that my life was bound to move to Toronto.

What was it about Toronto that made it feel like the perfect final destination for your musical journey, especially after living in so many iconic cities?

It’s definitely fate and destiny that has brought me to Toronto, which I can proudly call my home. Toronto and music have gone together in my mind for a long time—ever since I was a kid in Bowling Green, Ohio. That’s in America, otherwise known as the greatest country in the United States. Bowling Green is thirty minutes south of Toledo and an hour or so south of the Detroit/Windsor border. It’s about a six-hour drive to Toronto from Bowling Green. Since my early adolescence, Toronto and Canada were geographically and culturally on my radar, not only because I loved baseball and thought that the Blue Jays were pretty bad, but mostly because of the amazing popular music that came out of Canada and Toronto.

For example, when I was twelve, one of my favourite bands was the trio known as Rush. I used to sing “Fly By Night” with my friend, Billy, and we liked to copy Neil Peart’s massive drum solos with ridiculous air-drumming demonstrations. I learned that Rush was based in Toronto, and Canada and Toronto gained an aura of greatness in my mind. Also, in the mid-1980s, I loved to watch the Bob and Doug McKenzie television show on Canadian TV, which I was able to see in Ohio by fixing my TV antennae a certain way. It was totally different from anything I’d ever seen on TV in America, which, with few exceptions, was boring and full of mind-numbing commercials. By contrast, Bob and Doug McKenzie were endlessly entertaining and amusing. Those two were so silly and yet so serious, they loved to drink beer, and I just thought they were the funniest people I’d ever seen or heard. They’d sing, “Coooo-roo-coo-coo-coo-coo-coo-cooooo? Coooo roo-coo-coo-coo-coo-coo-cooooo”. It was like a call-and-response thing and I thought it was the most hilarious skit I’d ever seen. I must’ve sung or whistled those lines for two years straight. Bob and Doug even recorded a song called “Take Off (to the Great White North)” with Geddy Lee of Rush. I started equating Toronto with great music and having a good time, you know, having a lot of laughs.

Then, when I was sixteen, I got into folk music and the music of Bob Dylan and Neil Young. I just ate that shit up, like Neil Young’s double album, Decade. Oh man, I devoured that stuff, just loved it. Still do! That was another Toronto music connection, Neil Young. There was yet another Toronto music connection for me in Ohio. Finally, when I was seventeen, I went to a high school dance with a pretty girl named Lisa. I tried, and ultimately failed, to impress Lisa by playing Cowboy Junkies songs on my car’s cassette tape player. She dumped me a week later, but I still loved the Cowboy Junkies, who recorded their album, The Trinity Sessions, in Toronto. Thirty years later, in 2015, I had the great fortune of meeting Peter J. Moore in Toronto. He was the original recording engineer for The Trinity Sessions and later won a Grammy for his mastering of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes. Peter mastered my 2015 album, Poor Lazarus, my 2018 album, It’s a Blues World: Calling All Blues, and now the new album, Toronto Bound. He sadly passed away late last year, shortly after he finished mastering Toronto Bound. I’m proud to say that we were friends. We both loved playing blues harmonica. He lived just five minutes down the street from me in Toronto and we used to hang out and play the harmonica and mess around with vintage microphones and guitar amps from the 1950s.

Overall, I prefer Toronto over Chicago, New York, and Tokyo. It is a very cosmopolitan and worldly city, there’s all of the greatest Asian food I can dream of eating within walking distance of my house, and Toronto is not as insane or as violent as other cosmopolitan and worldly cities like New York. It’s also not as densely populated and busy like Tokyo. Even though Toronto can be cold in the winter and socially annoying because it’s so expensive and so many people here are super uptight and competitive about anything related to business or money-making, nonetheless, Toronto still is able to pull-off being a worldly city with a small-town vibe all at once. In Toronto, I can be anonymous when I want to be but also have the comfort of having great and dear friends in a small village-like environment. Last but not least, Toronto is chock-full of great musicians of all kinds. It’s a big honour for me to be able to play and record this album with such talented musicians who have made Toronto their home, namely Nichol Robertson, Victor Bateman, Lowell Whitty and Derek Thorne. They’re all incredible musicians and that’s what makes all of this fun and worthwhile for me, it’s to play with great musicians.

You’ve worked with legendary blues musicians like Tail Dragger Jones and Willie “Big Eyes” Smith. How did their influence shape the sound of “Toronto Bound”?

Those two musicians changed my life in profound ways. I feel lucky that I even knew them, let alone that I got to play in their blues bands. By the grace of some god, they both recognized in my harmonica playing that I had learned my blues harmonica style from the recordings of the great blues harmonica master, Little Walter Jacobs. When I was eighteen and nineteen, all I did in my spare time—after studying and after part-time work at a bookstore—was learn the harmonica playing of Little Walter, especially the songs he recorded with Muddy Water’s band in the early 1950s. I learned those songs on the harmonica, note for note, by copying Little Walter’s playing. I was obsessed. My friend, Dave Waldman, himself a great blues harp player in the style of Little Walter, had played harmonica with Taildragger since the 1970s, and he generously played the role of being my unofficial Little Walter harmonica coach. He’d show me many things on the harmonica so that I could play Little Walter’s harmonica parts correctly, e.g., all the different positions on the harp, the many techniques to make certain sounds, and so on. I learned about tone on the harmonica. I learned a lot from Dave, and I practiced every day with the old records until I could memorize and perform the Walter solos by heart. That process gave me great happiness.

One night, I went to hear Taildragger sing with my friend’s blues band, The Ice Cream Men. It was at Lilly’s in Lincoln Park, which is a very touristy area. The band kindly let me sit in on harmonica and Taildragger asked me, “Do you know ‘Baby, Please Don’t Go’?” I had learned that song by listening to Muddy’s version of the song with Little Walter’s harmonica parts, so I told him, “Yes, sir. I know ‘Baby, Please Don’t Go’”. I must’ve played it pretty well because, immediately after we concluded the song, Taildragger asked me if I would play harmonica in his band, The La-Z Boys. From that point on, and for three years or so, I played with him three or four nights a week, mostly on the West Side of Chicago at the 5105 Club or at the Delta Fish Market, located on the corner of Jackson and Kedzie. Both places were definitely not in the touristy part of town. Taildragger eventually said that I needed a stage name, mostly because I think he could never remember how to pronounce my last name—Kawashima. That’s a Japanese name that literally means “River Island”. Taildragger would routinely mess up pronouncing my last name when he introduced the band members to the audience. So, partly to avoid the embarrassment of messing up my last name, he decided to call me Sugar Brown because, in his words, “You ain’t black, but you definitely ain’t white….You’s Sugar Brown!” I could not find a reason to disagree with him on this point, so I accepted the name and I’ve been Sugar Brown ever since. Most people on the West Side, if they ever knew who I was, never knew my real name. They would just call me Sugar Brown. I just loved that. The most important lesson I got from Taildragger, as far as being a blues musician is concerned, is something that may seem like a very simple idea, but it’s something that, in actuality, is almost impossible to do without proper spiritual direction from a blues master. Taildragger would direct me and say, “Take yo’ time! Take yo’ time! Take yo’ time!!!”

As for Willie ‘Big Eyes’ Smith, he was the drummer in Muddy Waters’ band for over thirty years. His son, Kenny Smith, now an internationally famous blues drummer, was also in Taildragger’s band, The La-Z Boys. I was very fortunate to have been in the same band with Kenny Smith, along with my university friend and bandmate, (Rockin’) Johnny Burgin, who’s also an internationally renowned and touring bluesman. When I was nineteen, Kenny was probably fifteen or sixteen, legally probably too young to even be in the clubs we were playing in. I lived on 51st and Greenwood in Hyde Park, and Kenny and Willie Smith lived around 43rd street in Woodlawn, just five minutes from my apartment. So, every Wednesday evening, I’d drive my little Ford Escort to Willie’s house and pick up Kenny and his drum set and go to the Taildragger gig together. Every week, I’d bring my harmonicas, my mic, and a 1967 Fender Super Reverb amp, which I bought for $400. We’d do the gig from 8pm till 2am. It included a hot meal and Taildragger would pay us $35 as sidemen. I began singing a few songs, like Little Walter’s “Blue and Lonesome”, “My Babe” and “Had My Fun”, but I wasn’t writing or singing my own songs yet. I was still learning the classic blues songs. After the gig, we’d go and eat hot dogs on Maxwell Street, and then I’d drop Kenny off at his house around 3am. That’s how I met Willie, who’d often be awake, having himself just returned from a gig of his own somewhere else. I tried not to act too star-struck while we smoked cigarettes on his porch.

To my amazement, for a short stint in the summer of 1993, Willie asked me to play harmonica in his band, The Legendary Blues Band. We did small, local gigs around Chicago, including a memorable wedding gig, which initiated me into the world of smoking reefer in the band’s van between sets. I’d never even seen reefer before then, let alone smoked it. I’d grown up in Ohio during the conservative Reagan years, when Nancy Reagan instructed the nation to “Just say ‘No’ to drugs”, apparently because they were illegal, dangerous and could make you crazy. As a kid, I thought this was a pretty sensible position to take, and I continued to think this way, basically until I played in Willie’s band. So, when the joint was passed over to me in the van on that wedding gig outside of Chicago, I said to Willie, “Whoa, man—this is marijuana! This is illegal, dangerous, and can make you go crazy!” They all laughed at me. Willie said, “Ken, don’t you know that Muddy smoked reefer all the time? Haven’t you heard his song, ‘Champagne and Reefer’?” I had not heard that song at that point in my life and I was speechless. I couldn’t believe that Muddy Waters himself smoked reefer. But I thought, “Well, if Muddy smoked it, I guess I should, too!” It was one of the best decisions I ever made in my life. To go back to Willie, the important thing is not about the reefer, which is great, but rather that I learned, through his example, what kind of beats Muddy himself liked to play his blues songs to, what kind of beats Willie Smith, Little Walter, James Cotton, Pinetop Perkins, and Otis Spann liked, basically what beats Muddy’s band liked to play, especially those driving blues shuffles. Willie is the essence of Muddy’s shuffle beat; that shuffle finds its essence in Willie. And let me tell you, it’s a huge beat, a beat I’ve been chasing after ever since. I learned so much about the blues from Willie and Kenny Smith just by playing with them. It taught me the joy of playing with a great drummer who can really drive a song. Willie drove the songs with such power and grace, and he carried the groove so assuredly and confidently, that the rest of us could play our own instruments freely and without the slightest fear. Playing with him was like being part of a powerful locomotive engine, and he was the train’s engineer. His playing made me fearless.

You ask if Taildragger and Willie Smith influenced the sound of my new album, Toronto Bound? I would say, Hell, yeah! Taildragger gave me the name Sugar Brown, which I still go by, and he taught me how to ’take your time’, which I think I did on the new album. And Willie taught me how to be fearless, which I like to think comes out in the songs. Taildragger and Willie also encouraged me to keep playing the blues harmonica, which I continue to do, and in ever-changing ways, on Toronto Bound.

What does it mean to you to be a blues musician in Toronto, and how does the city’s culture and music scene influence your sound today?

It’s a cliché to say that Toronto is multi-cultural and cosmopolitan, but it’s true. Toronto is full of people who have immigrated to Canada from all over the world, especially from the global South. For the vast majority of them, they work jobs for cheap wages in the ever-expanding service sector. As a result of this national labour policy, essentially, people from all over the world come to live and work in Toronto. Racially speaking, it’s a multi-cultural and mixed city, which is something I like about Toronto. Because it’s multi-racial, I feel comfortable in my own skin, so to speak, and I don’t feel excluded or stared at annoyingly by people who are surprised or shocked to see an actually existing Asian person speaking in perfect English. I had enough of that shit in Ohio. Multiculturalism is like an official ideology of the city, and in many ways, I’m all for it.

At the same time, the unofficial reality is that, while there is a beautiful diversity of ethnicities here, Toronto can also be a very segregated town with huge disparities and inequalities between the super-wealthy, who are usually white folks, and the vast majority of relatively poor folks, who are typically racialized people. There are lots of poor white folks, too, of course, in both the city and the countryside. There are also a lot of unhoused people in Toronto who are forced, because of the ludicrously high prices of the city’s real estate market, to live on the street or in tents. The official ideology is that Toronto is super prosperous and rich and that all kinds of people—black, white, Asian, brown, native, or whatever—can all be successful. But the reality is that most people here are not rich at all, racism continues to exist in countless situations and institutions, and financial security and everyday happiness is a fleeting dream for most. As a result, lots of people in Toronto have or get the blues, which stems—according to Howlin’ Wolf, at least— from a condition of not having enough money to survive and lead a secure and dignified life, a condition that also has everything to do with systemic racism in the so-called free market. It should be clearly said that the blues is fundamentally a musical expression of protest against racism and poverty. Of course, the blues also comes from broken hearts. Toronto definitely has a lot of broken hearts, I can assure you, there’s no shortage there! You combine this with a widespread condition of not having enough money to pay for basic expenses like rent, plus the racism and white supremacist junk, well, then you got a whole city full of the blues. Add to this the ruinous social effects of financial and commercial crises, and now you also got a lot of unemployed people. That’s why they don’t have enough money to live. Then you know they got the blues. So, the blues is everywhere in Toronto, for better and for worse, even if the official ideology tries to hide this. But the blues is so irrepressible in its frank truthfulness that it can easily explode these sugar-coated clichés.

In Toronto, there’s a vibrant Caribbean immigrant community from Jamaica, Trinidad, Barbados, Guiana, and other countries in the Caribbean. Caribbean culture, including its diverse and rich styles of music, is found all over Toronto, and it’s deeply connected to the African diasporic community. About twelve years ago, I began listening to the music of Fela Kuti, which introduced to me the drumming of funky Lagos and in West Africa, more broadly. I loved it so much that I began taking djembe lessons at a local African drum shop in Toronto, on Dundas Street. During those lessons, I was first able to hear the dun-dun drums, or the African bass drums, along with twenty other djembe players. The sound and beats just blew my mind. I could no longer hear songs in my head without these African drums, and felt a powerful need to integrate those beats directly into the songs that I was composing and that eventually found their way onto Toronto Bound. By a stroke of good luck, I ran into Derek Thorne, a Trinidadian djembe player, and fellow Torontonian who knows the African drumming scene in the city extremely well. I asked Derek if he would play the dun-duns and the djembe on the new record (of course, not at the same time), and alongside Lowell Whitty on his drum kit. He agreed and Lowell was also down with the idea. They work beautifully together. Add to this mix Victor Bateman, a long-time Toronto bassist, and improvising maestro, and Nichol Robertson—arguably one of the most imaginative and lyrical, if not hardest working, guitarists in the city—and you’ve got what I think is a great Toronto blues band.

As the child of a Japanese father and Korean mother, how has your cultural heritage impacted your approach to the blues, a genre rooted in African American history?

When it comes to my relation to blues music, and also how the blues world and the blues industry often represent my relation to the blues, at least in Canada, what I have noticed is that the topic of my Asian heritage—that is, the fact that I am part Japanese and part Korean—tends to commonly overshadow the fact that I was born in the U.S., that I am originally an American, and that I’m a Canadian citizen. It often goes unthought and unmentioned that my Asian heritage is quite accidental to my musical production as a blues artist. I mean, if my Asian heritage really did influence my musical work, I suppose I would have tried to sing Korean pansori or Japanese enka songs, which I both love, but the simple truth is that I prefer to sing the blues. In any case, in the blues world, especially in North America, my Asian heritage is, to say the least, both a blessing and a curse. I would prefer not to be known, heard, or listened to, as a blues musician, simply because I’m Asian, and I would prefer not to be reduced to the question, “Oh, yeah, you mean that Asian blues guy?” I would much rather prefer people simply say, “You gotta hear Sugar Brown!” The problem is that, from a strictly marketing perspective, this kind of racializing narrative, especially as it is routinely spun within a liberal, multicultural, and national media-scape, apparently seems to get lots of people talking and buying lots of stuff. It seems to sell commodities and make money, or so the fantasy goes. Of course, I’m not going to quit my day job anytime soon. What I’ve learned is that, if you do jump into this kind of ideological space of the market, and you’re an Asian-American-Canadian blues musician like me, you’d better not only be able to play good music and deliver a good show; you also better have thick skin and be mentally prepared to be represented—by people whose intentions, actions and words are quite beyond your control—as a kind of cultural improbability. But there are worse things in life than this!

When I first started playing the blues in Taildragger’s band on the West Side of Chicago, I was, almost without fail, the only Asian person in the club, and probably in the entire neighborhood. In that regard, it was like being back in Ohio, where I was usually the only Asian person in the room, except that in Ohio I was always in a sea of white people. On the West Side of Chicago, I was among all black people, by and large. Of course, there were a few interesting white people there, who knew where to go to hear great live blues bands in black Chicago. Once in a while, a few tourists and die-hard blues fans from Japan would come to the black blues clubs on the West Side of Chicago; they also knew where to go to hear the real lowdown and funky blues.

Of course, from the outset of my time in Chicago, I knew and understood that blues music was the music of and by black people, that it was a black musical expression and style, alongside jazz, funk, soul, and hip-hop, of the historical and political struggles of black folks against oppressive Jim Crow laws, against poverty in the big city and against all the anti-black police killings that went on during and after the Great Migration of black folks from the rural south to the industrial north, between the 1920s to the 1960s and after. I took it as an unquestioned and unshakeable truth that the blues music of Muddy Waters and Little Walter, Howlin’ Wolf, Rice Miller, and countless others, represented not only heartfelt but also rebellious and daring songs of protest against everything that was evil, unfair, racially discriminatory, and basically low-down and mean. Singing the blues is liberating because it speaks out against those problems publicly, in song and verse, and it allows everybody to understand their own suffering to these problems as universal. In the blues, you never feel alone, even if we cannot help but suffer one by one. So, I always gave massive respect to the black folks who played and enjoyed the blues, and I was convinced that they would not be mean or discriminatory towards me, as long as I could demonstrate that I, too, had the blues. At least my music should prove it, I thought. This seems to have worked for me, and in Chicago, I always felt accepted by the black blues communities that I socialized and played with. That made me feel really good and dignified, as a person and as a human being, and I was proud to be part of the black blues community, proud to play with and for black folks. That good feeling dwells in my heart to this day and it constantly influences the way I compose, play, and sing my blues songs.